Author: Andres Vaamonde

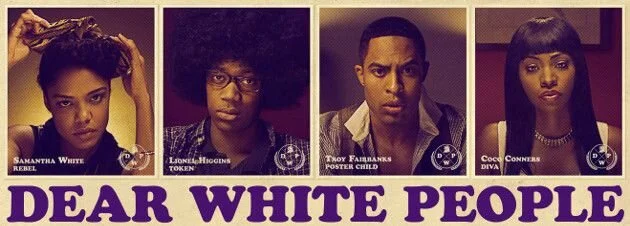

Dear White People is hilariously awkward. Justin Simien’s feature length debut (currently playing at Cinemapolis) generates gut-bubbling discomfort. Samantha White, played by an elegantly fierce but ultimately fragile Tessa Thompson, is a student at Winchester University dissatisfied with racial relations at her Ivy-akin school. She hosts a radio show that publically confronts stereotype and prejudice both on campus and in society at large–often confrontationally and always hilariously. Simien utilizes the thematic device of the radio show to great aplomb. The barely-30-year-old’s witty writing simultaneously unveils harsh truths while still smiling a face full of comedy. “Dear white people: the official number of black friends you are required to have has now been raised to two” White muses. “Sorry, but your weed man, Tyrone, does not count.”

Comedy notwithstanding, Dear White People is a movie about conflict and opposition, extremes and absolutes. Racially divisive power struggles between students and administrators alike dot the generally coherent plot. Though the language adjusts between the colloquial spitting of college kids and the reserved “isms” of academia, a layer of vitriol lines the linguistic coating of Dear White People. Furthering the absolutism of the film, characters themselves generally reside within cookie-cutter molds–the radical Black Panther, the snobby white boy, and the out-of-touch administrator all play pivotal roles. Simien’s cinematography also promotes adversarial vibes by often symmetrically framing oppositional groups against one another.

Though soaked in black and white, Dear White People does not solely remain focused on polarized absolutes. Simien’s film explores the confused middle as well through the misfortunate adventures of disillusioned freshman Lionel Higgins played by an endearing Tyler James Williams. Crowned with white-finger-encroached hair, Lionel balances much upon his bulbous Afro. With a mixed racial identity and ambiguous sexual orientation he struggles mightily to locate home within the neatly divided world of Winchester.

Simien wields Lionel with a master’s touch and to far more nuanced value than any other character. Due to Lionel’s vague and lonesome existence, he resides most comfortably in the empathetic heart of the viewer. When the black student union questions Lionel’s loyalty by asking him if it is more difficult fitting in with the white community or the black community, and he despondently whispers, “neither”, compassion swells. Lost in a sea of extreme, the viewer grasps tightly to the aimlessly floating buoy of Lionel. Thus, selecting him to be the ultimate instigator of the racially charged brawl at the conclusion of the film truly jars the audiences in the most successful way. We of course still root for our hero, but where comfort once lived discord now reigns. This shift is a wonderfully executed, culture-reflecting metaphor on behalf of Simien. The audience’s (specifically the white audience’s) unconscious discomfort with Lionel’s grope for empowerment speaks incredibly to modern racism–radicals are okay as long as we don’t have a personal connection. This subconscious trick of Simien’s lifts his junior effort beyond the realm of elementary slapstick to poignantly disruptive satire.

But let us not get ahead of ourselves. Dear White People certainly bears a few stains on its otherwise thoroughly immaculate exterior. First of all, we are led to believe that the students at Winchester, in addition to succeeding highly in academics, all retain part-time gigs as runway models. Not that beautification is a unique sin to Simien (nearly all of Hollywood chokes on this monetarily focused component), but for a film supposedly focused on “authenticity” the physical appearance of its actors is anything but authentic. Dear White People occasionally dips into the metaphorically overdramatic, such as in a near final scene in which White and her pasty beau Gabe (played by a slightly boring Justin Dobies) finally patch their frayed relationship. As they walk into the proverbial sunset, the camera focuses on Gabe holding the newest issue of the fictitious Independent Observer with the headline “Ebony & Ivory”–except…wait for it…he’s holding it upside down! What symbolism. Simien lets us know how dislocated race relations have become at Winchester with the subtlety of Kim Kardashian’s minstrelized buttocks.

Of course, this article has yet to broach the throbbing question regarding this film: Does Cornell suffer from the same diseased racial climate as Winchester? Many obvious similarities can be drawn between the two schools. Both are reputable and historic academic institutions with a dramatic socio-economic gradient. Both Samantha White and Kurt Fletcher (the instigating, privileged Caucasian lead of Dear White People) call our gorges campus home. However, one enormous difference remains. At Cornell, Samantha White doesn’t have a radio show. At Cornell, the race discourse is but a hushed whisper. Deafening silence replaces dialogue.

Think about it. How often do you hear issues of race being discussed on campus? I asked students of varying racial identities this very same question and their responses often amounted to a shrug or a sigh.

“I honestly don’t think it’s such a big problem,” said one white student who I will blanket in anonymity. “People are just too busy.” This point of view was not racially specific, either. Some students of color even responded with a similarly indifferent air.

The unfortunate truth is that the uninspired atmosphere on campus supports this notion–that there simply is not a significant display of pro-activeness. I reached out to multiple Black student groups for commentary and did not receive even a word of reply. I reached out to a professor of Africana studies to the same fruitless end.

Cornell students might simply be too overworked to dedicate time to the issue of race but that does not mean that there is no issue. Even if Cornell is not as dramatically divided as Winchester, problems still exist. Cornell suffers from racial prejudice just in a less egregious format–which is not a caveat in the slightest. Inflamed bigotry should not be the determiner of inequality. Racism on modern campuses has far less to do with the “n” word and far more to do with the white-washed yearbooks of the fraternities and sororities that dominant the slope.

Perhaps the most uncomfortable and burdensome part of Dear White People reveals the continued necessity for an open dialogue about race on college campuses. Amidst credits come appalling photos of greek parties from schools across the country. Smiling “blacked-up” faces flash across the screen to a chorus of boos and gasps from the predominantly white crowd sitting in Cinemapolis. What is most shocking about these photos, though, are the years associated with them: 2012, 2011, 2014. The inclusion of these glances into the underbelly of collegiate racism announces louder than any of Dear White People’s quick-witted dialogue could that race is still an issue on university campuses. Still.