Author: Yvette Ndlovu

A troubling incident happened to me recently. It was during a video chat with one of my relatives. We had been chatting for a bit when I suddenly couldn’t think of anything to say. I tried to maneuver my way out of the inevitable awkward lull by mumbling a few words about the weather, but my relative didn’t get the hint. Instead, to my chagrin, they said this:

“You’ve gotten so fat.”

The comment was seemingly small and harmless, but it stung nonetheless. In the college world, the Freshman 15 may as well be the Red Scare. As a second semester freshman, I live with this hanging over my head. Most of the time, the hustle and bustle of college helps me to forget that this burden even exists. But then someone throws a snide remark about my growing waist, double chin or cheeks, and snaps me right back to reality.

The sensible reaction to this body-shaming would be to dismiss it and move on with my life, but words leave an imprint. Instead, I shrunk away from food, excusing myself from dinner with friends by alleging that I was too busy with assignments. When I eventually could not avoid eating with my friends, I made sure they saw me eat to overcompensate for the reality that I was starving myself. Everyone knows that I’m the kind of person who gets a whole sub, chicken fingers and a soda at Nasties. No one would suspect that I have an overwhelming fear of eating, such that eating is like going to war and the dining hall is my battlefield.

The comforting yet sad reality of my struggle is that I am not alone. Show me someone who is completely satisfied with their body, and I’ll show you crickets. Currently, 80 percent of women in the U.S. are dissatisfied with their appearance. And more than 10 million suffer from eating disorders. This reality was one of the motivations behind Victoria’s Secret model Cameron Russell’s TED Talk “Looks Aren’t Everything, Believe Me, I’m A Model”. The talk discusses the power of image, and how even those perceived to have ideal body types fall into the bracket of women with crippling self-esteem and self-image anxieties.

So what exactly drives this self-loathing when girls hit their teens? The answer is… society. Consciously or not, we’ve all contributed to building this culture that discriminates against others because of their body type. Body shaming propels women to obsess over numbers on a scale because a woman’s body mass has become synonymous with a measure of her self-worth.

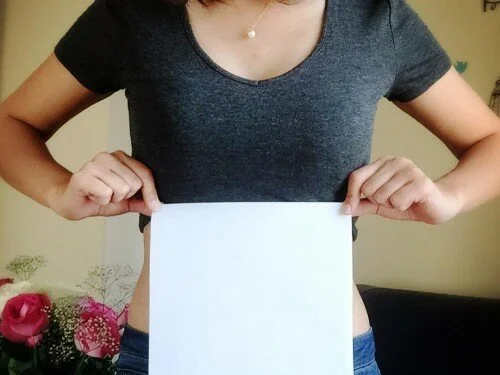

Social media reinforces such ideals of beauty. Campaigns such as “Project Harpoon”, “ThInner Beauty”, for instance, Photoshop pictures of plus size women to motivate them to lose weight. The idea is to show them the “difference between how they are and how they could be.” There is also the Twitter campaign dubbed “A4 Paper Challenge,” in which women take photographs of themselves holding an A4 printer paper in front of their waists. If the paper does not cover their waist, they are considered fat and have thus failed the challenge.

These trends highlight the harmful ideals surrounding beauty which leads girls to take extreme measures to be literally paper thin. Project Harpoon’s Facebook page has since been taken down, but the damage is still there. The fact that a “project” like this existed at all underlines the ludicrous beauty standards that shame people to try to fit into a very small box.

These standards exist in every society, though they may differ across cultures. The most ironic part of my personal body-shaming incident was that the same person who called me out on my apparent weight gain had accused me of looking “un-African” because of how thin I looked in previous conversations. Eating disorders are considered rare amongst black women because black women are not allowed the luxury of having body image issues. It is assumed that black women love being big and beautiful, and have an innate confidence that encourages us to celebrate our curves. This idea is constantly peddled in music videos, on television, on social media and everyday conversations.

But this is a myth. Many of my black female friends who fall on the thinner side have confessed to overeating because they felt pressured to attain the classic “black” features such as the big booty and hips. On the other side, my thicker friends pretend to love their bodies, but taunts about their weights have led them to follow strict diets behind closed doors. I’ve wrestled with being both being underweight and overweight. But to mention this problem in my community is taboo. Preoccupation with weight is considered a “white people problem,” and black people have bigger problems to tackle above a seemingly obscure and privileged dilemma. Yet insecurities, especially those about our bodies, affect us all; ignoring that only exacerbates the problem.

As I prepare to enter my twenties, I want to use my experience to help to make a change. I’m starting with the girl in the mirror by accepting myself, accepting others, and accepting that there will always be critics, no matter how I look. This criticism should not chain anyone to a scale or compel them to take drastic measures to conform to someone else’s definition of beauty. At the end of the day, the most important thing to do is love yourself – because you are not going anywhere.